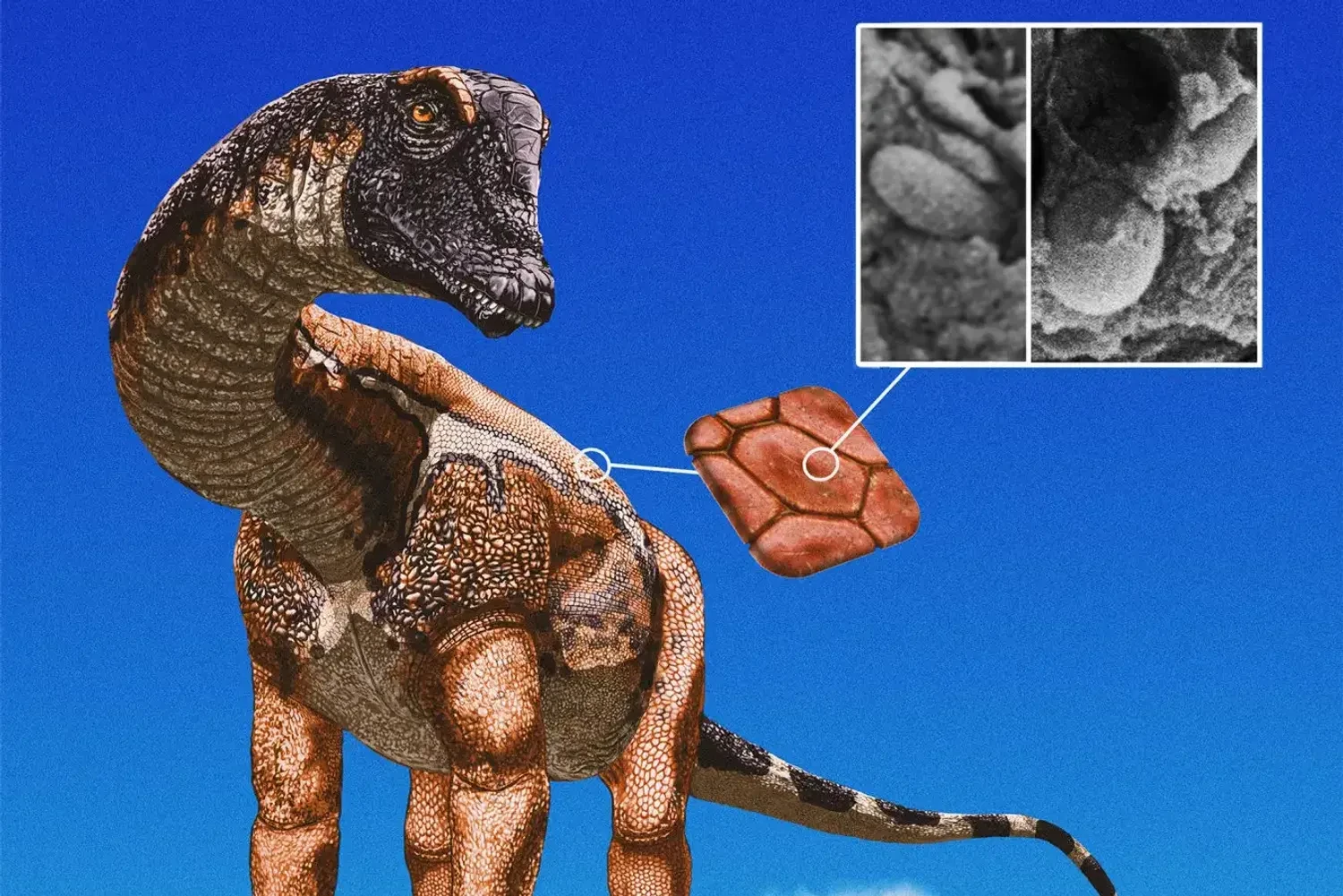

New research by a Bristol MSc in Palaeobiology student shows that sauropod dinosaurs had colour-bearing melanosomes in their skin. Tess Gallagher and colleagues studied fossilised sauropod skin remains, approximately 145 million years old, collected in 2019 and 2022 at the “Mother’s Day” quarry in Montana.

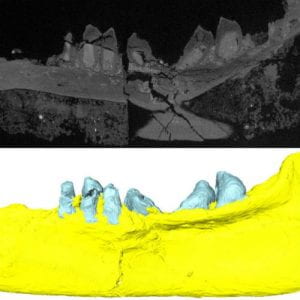

Although the fossil remains cannot be definitively identified, they might have belonged to a Diplodocus. Tess took tiny samples from four scales using a scalpel and then examined them with a scanning electron microscope, which allowed her to see details at the cellular level. The skin was preserved in three dimensions, not just as an imprint, says Gallagher.

It also showed the presence of various melanosomes — structures within cells that store melanin and form the color of skin, hair, eyes, and feathers. “I expected to find at least traces of melanin,” she says. “But we found evidence that sauropods could have different forms of melanosomes, which ultimately means the potential for diverse colours.”

Melanosomes were present in every sample studied, and they belonged to two main types: elongated and disc-shaped. However, it is currently impossible to say exactly what colours the skin of these sauropods might have been — only that the variety of structures indicates several possible shades.

The closest analogy to disc-shaped structures are the platelet melanosomes found in the feathers of modern birds. Gallagher says they may indicate Diplodocus‘ ability to create a variety of colors using its melanosomes. “These animals could have had much more distinct color patterns, rather than being gray, as they were often depicted in old palaeoart.”

Read the paper here.

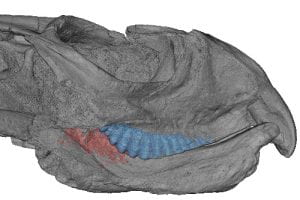

Bristol MSc student Thitiwoot Sethapanichsakul published the second paper from his MSc thesis, about the internal structure of tooth replacement in rhynchosaurs, a group of reptiles that walked the earth between 250-225 million years ago, in the Middle and early Late Triassic, before being replaced by the dinosaurs.

Bristol MSc student Thitiwoot Sethapanichsakul published the second paper from his MSc thesis, about the internal structure of tooth replacement in rhynchosaurs, a group of reptiles that walked the earth between 250-225 million years ago, in the Middle and early Late Triassic, before being replaced by the dinosaurs.

Since he graduated in 2021, Will Richardson writes that he has been working as a lava cave tour guide in Iceland, inside Víðgelmir lava cave. Here he is (left) in a spectacular view.

Since he graduated in 2021, Will Richardson writes that he has been working as a lava cave tour guide in Iceland, inside Víðgelmir lava cave. Here he is (left) in a spectacular view. Thomas Farrell who completed the Palaeobiology MSc last year has been awarded the Geologists’ Association Curry Prize for his thesis: “New ecdysozoan worms from the Sirius Passet Lagerstätte and their implications for the evolutionary history of Ecdysozoa.” The project was supervised by Jakob Vinther.

Thomas Farrell who completed the Palaeobiology MSc last year has been awarded the Geologists’ Association Curry Prize for his thesis: “New ecdysozoan worms from the Sirius Passet Lagerstätte and their implications for the evolutionary history of Ecdysozoa.” The project was supervised by Jakob Vinther.

Harriet worked on specimens from Bristol City Museum as well as newly collected materials. During field work, Harriet noted large numbers of burrows and trails made by worms, clams, and king crabs. In fact, the king crab tracks and resting marks show that this had become a tidal zone, where the sea flooded in and out.

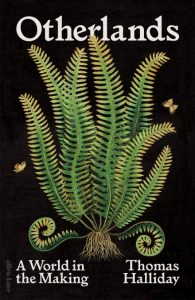

Harriet worked on specimens from Bristol City Museum as well as newly collected materials. During field work, Harriet noted large numbers of burrows and trails made by worms, clams, and king crabs. In fact, the king crab tracks and resting marks show that this had become a tidal zone, where the sea flooded in and out. om Halliday, who completed the MSc in 2011, has just published his first book, ‘Otherlands’ to high critical acclaim. The publisher, Allen Lane-Penguin, provide this blurb, “Otherlands is an epic, exhilarating journey into deep time, showing us the Earth as it used to exist, and the worlds that were here before ours. Travelling back in time to the dawn of complex life, and across all seven continents, award-winning young palaeobiologist Thomas Halliday gives us a mesmerizing up close encounter with eras that are normally unimaginably distant.

om Halliday, who completed the MSc in 2011, has just published his first book, ‘Otherlands’ to high critical acclaim. The publisher, Allen Lane-Penguin, provide this blurb, “Otherlands is an epic, exhilarating journey into deep time, showing us the Earth as it used to exist, and the worlds that were here before ours. Travelling back in time to the dawn of complex life, and across all seven continents, award-winning young palaeobiologist Thomas Halliday gives us a mesmerizing up close encounter with eras that are normally unimaginably distant. Other papers include Natasha Howell’s project on aposematism in mammals, published in Evolution, Giacinto de Vivo’s study of function in the anomalocarids, giant Cambrian predators, and Karina Vanadzina’s study of developmental change in planktic foraminifera during a speciation event.

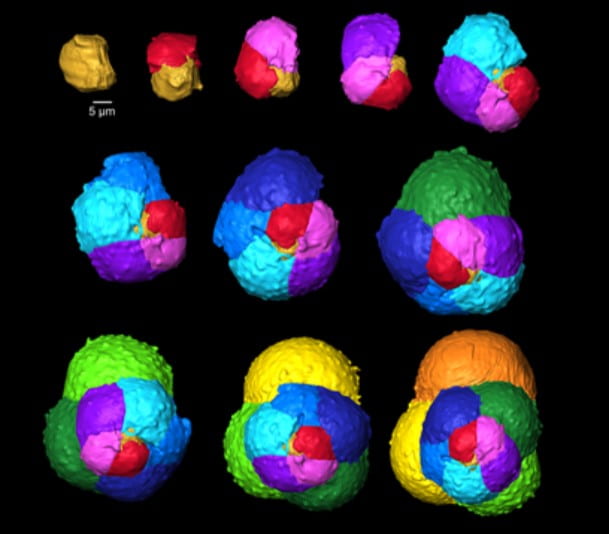

Other papers include Natasha Howell’s project on aposematism in mammals, published in Evolution, Giacinto de Vivo’s study of function in the anomalocarids, giant Cambrian predators, and Karina Vanadzina’s study of developmental change in planktic foraminifera during a speciation event.

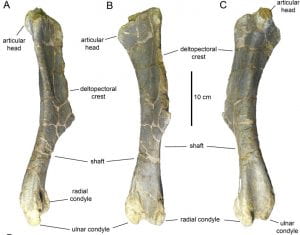

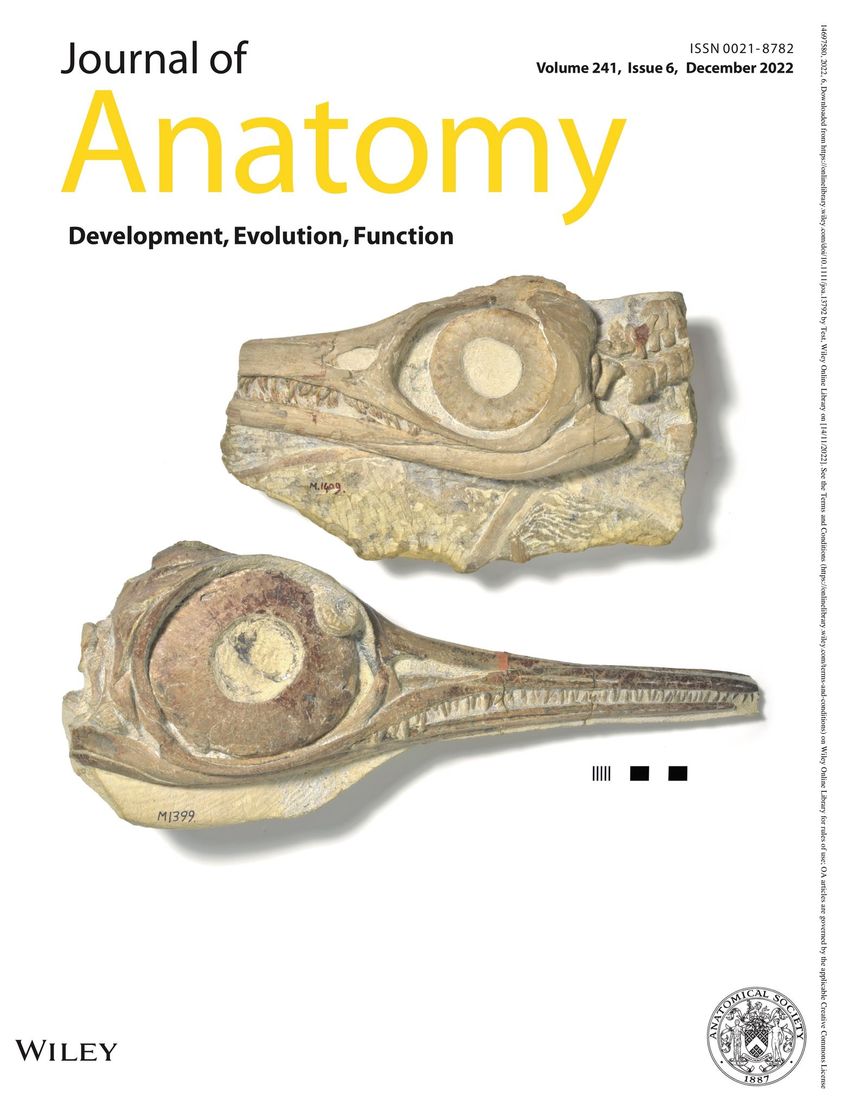

Congratulations to Sam Coatham who has published his MSc research on Titanichthys – a giant armoured fish that lived in the seas of the late Devonian. Sam’s work has shown that Titanichthys fed in a similar manner to modern day basking sharks. The research has attracted lots of media attention. You can read a summary

Congratulations to Sam Coatham who has published his MSc research on Titanichthys – a giant armoured fish that lived in the seas of the late Devonian. Sam’s work has shown that Titanichthys fed in a similar manner to modern day basking sharks. The research has attracted lots of media attention. You can read a summary